Are video games making players violent?

March 21, 2018

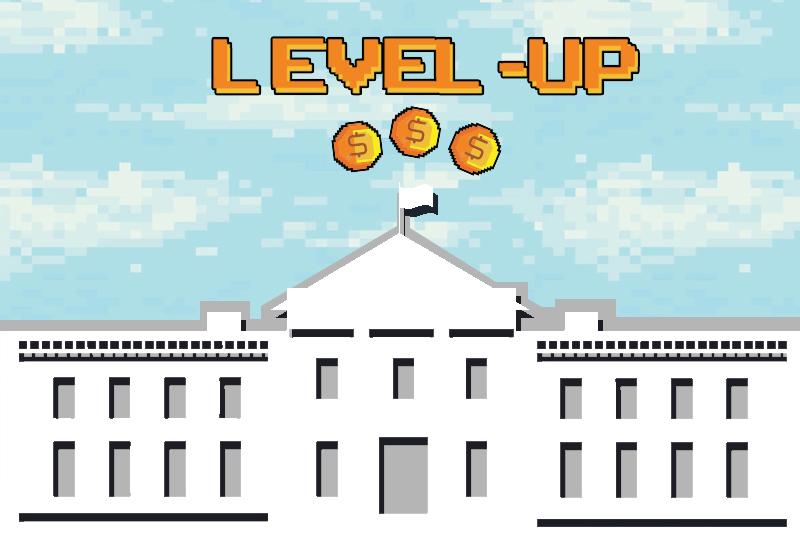

On March 8, 2018, the White House released a video displaying graphic scenes of violence from video games. This compilation has since led to major criticism from its viewers. The video was published after officials cited video games as a source of growing violence in our society and suggested that they were partially a cause in recent school shootings.

A large issue with this video is context. Not much has been disclosed about the sources of the graphic scenes shown with the video itself being basic and lacking substantial supporting information. The majority of scenes shown in the video happen to come from the “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare” series, which is commonly a target for gaming critics. Other game scenes appear to come from “Fallout 4,” the “Wolfenstein” series and “Friday the Thirteenth: The Game.”

These games do indeed focus on war, horror and other adult themes. However, the violence in these games isn’t just random killing: it shows the horrors associated with these topics. If players bought a game about “Modern Warfare,” they should expect that there will be death. The scenes the White House including in their video all have important messages about terrorism, corrupt governments and human suffering.

Without the essential context for why there is violence in these scenes, the non-gamer might seem them as mindless bloodshed and horrific images. “No Russian,” a scene included in the video, comes from “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2” and features a terror attack orchestrated by Russian terrorists to perpetuate a war with the United States. The scene is meant to make the player feel uncomfortable, and it even has options to not shoot civilians or to skip the mission entirely.

In an interview with GamePro in 2009, Jesse Stern, the games script writer, explained the intent the developers had when they created this scene.

“These are human beings who perpetrate these acts,” Stern said. “So you don’t really want to turn a blind eye to it. You want to take it apart and figure out how that happened and what, if anything, can be done to prevent it. Ultimately, our intention was to put you as close as possible to atrocity. As for the effect it has on you, that’s not for us to determine.”

All of these games have been given “M” ratings, which require the purchaser to be over 17 years old. In addition, modern consoles have an option that allows parents to completely block this content from certain accounts. The reality is that viewing this media is just as hard as sneaking into “R” rated movies or buying cigarettes especially if parents remain aware of what their children are buying and using.

The games shown contain no more violent than a typical “R” rated movie. Films such as “The Revenant,” which have won countless awards and critical praise, show equally graphic scenes. These stigmas against gaming had been used against films for years, yet today we actively award violent movies as being art pieces. Gaming culture, and by extension many game developers and players, have been focusing their efforts on ending these stigmas and helping their own communities. For example, Checkpoint, an Australian government side project, is dedicated to spreading information about mental health issues and finding ways for games to help treat them. They offer extensive descriptions of what psychological issues you may be facing, treatment methods and ways to overcome your struggles.

“Gamers Fighting Depression,” a Discord server dedicated to helping game players overcome depression, is a volunteer community of fellow game players helping others deal with their issues as quickly as possible. The community offers friendly faces and a safe place to talk, and the group chat can be a positive force that an endless amount of people can access.

In addition to this community support, there are games that do not use violence as a means of solving problems. In 2015, “Undertale” was released to fan acclaim and critical praise for its unique spin on problem solving in a role playing game (RPG). Rather than slaying every enemy in your path, developer Toby Fox implemented the mechanics of befriending your adversaries instead of harming them. By hugging and talking to the monsters you face, the player is made aware of the creature’s feelings and emotions.

With all of the other issues facing America, violence in video games would seem to be far below those of school shootings, North Korea and many others. Attacking video games as the problem when research has shown that they are not a source of inducing violence seems to make this effort more of a distraction than a solution.

Anonymous • Mar 21, 2018 at 11:37 am

UNDERTALE IS THE BEST GAME EVER SO PLEASE LEAVE VIDEO GAMES OUT OF IT TOBY FOX WORKS BETTER THAN YOU

Anonymous • Mar 21, 2018 at 11:36 am

video games have nothing to due with the school shooting or violence nothing you are just looking for something to blame gosh youre so stupid