Study: People who live in colder, darker climates drink more

November 23, 2018

PITTSBURGH — According to a new study released by UPMC, people who live in colder, darker climates drink more alcohol.

The study conducted by the University of Pittsburgh Division of Gastroenterology states that people living in colder regions with less sunlight drink more alcohol than those who live in warm-weather regions.

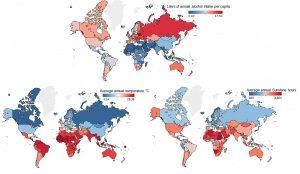

The study, which was published in Hepatology, linked a decrease in temperature and amount of sunlight hours with an increased consumption of alcohol. According to the study, climate factors were also linked to binge drinking and the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease, which is one of the main causes of death in patients with extended excessive alcohol use.

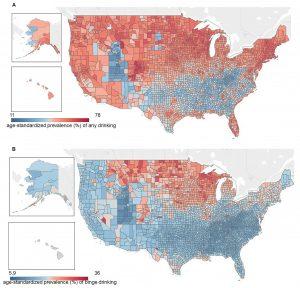

“It’s something that everyone has assumed for decades, but no one has scientifically demonstrated it. Why do people in Russia drink so much? Why in Wisconsin? Everybody assumes that’s because it’s cold,” said senior author Ramon Bataller, M.D., Ph.D., chief of hepatology at UPMC, professor of medicine at Pitt, and associate director of the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center. “But we couldn’t find a single paper linking climate to alcohol intake or alcoholic cirrhosis. This is the first study that systematically demonstrates that worldwide and in America, in colder areas and areas with less sun, you have more drinking and more alcoholic cirrhosis.”

The study also linked depression to drinking alcohol, which tends to be worse when sunlight is scarce and temperatures are lower. Using data from the World Health Organization and the World Meteorological Organization, Bataller’s group found a clear negative correlation between climate factors and alcohol consumption, binge drinking and alcoholic liver disease.

“It’s important to highlight the many confounding factors,” said lead author Meritxell Ventura-Cots, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher at the Pittsburgh Liver Research Center. “We tried to control for as many as we could. For instance, we tried to control for religion and how that influences alcohol habits.”

The study suggests that research proves police initiatives aimed at controlling and minimizing alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease should target areas where alcohol is more likely to cause problems.

To read to the full study, click here.